By Associated Press’s Kate Brumback

Ruby Robinson went to Detroit’s immigration court a few days after President Donald Trump’s second inauguration to post a notice that his organization’s deportation assistance desk was no longer open.

Following a Trump executive order that directed the Justice Department to direct nonprofit groups to cease operations immediately on four federally sponsored programs that offered information to individuals in immigration proceedings, the Michigan Immigrant Rights Center desk was shut down.

According to Robinson, managing attorney for the center, which has served roughly 10,000 people since it started running the help desk in December 2021, there were folks in the waiting room that we ordinarily would have been able to help, but we’re not able to do so at this moment.

Many will wind up navigating the system alone if there are no programs that inform individuals in immigration courts and detention facilities about their rights and the intricate legal process. Advocates fear that as Trump attempts to fulfill his campaign pledge to tighten down on illegal immigration, due process and the backlogged immigration courts will suffer.

A lawsuit opposing the stop-work order and calling for an immediate restoration of program access was filed Friday by a consortium of nonprofit organizations who offer the services.

The day after the Jan. 22 stop-work order, Amica Center for Immigrant Rights personnel traveled to a detention facility in Virginia to deliver services despite the absence of federal funding. According to Amica executive director Michael Lukens, who called the stoppage “devastating,” they had spoken to roughly two dozen people before being removed out by detention center authorities who informed them they could no longer perform those services.

We frequently hear that people are unaware of what is going on. For what reason are they being held? What will take place next? According to Lukens, we are being prevented from providing even that fundamental degree of guidance.

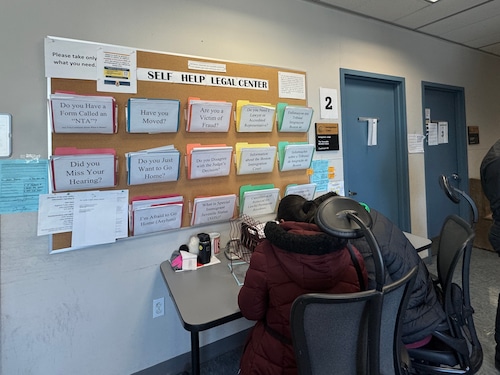

Attorneys operating ahelp deskinside In 2024, more than 2,000 persons received services from Chicago’s bustling immigration court. Initiated with private donations in 2013, the National Immigrant Justice Center extended the initiative with federal monies three years later.

The organization has reduced its services since the stop-work order, but spokesperson Tara Tidwell Cullen stated that they are not sure how long they will be able to do so given the void left by government funding cuts.

Posters alerting people to their services and legal help hotline information have been taken down from prison facilities, according to a number of groups.

Lukens stated that the programs have widespread bipartisan support and that Congress allots $29 million annually for the four programs: the Legal Orientation Program, the Immigration Court Helpdesk, the Family Group Legal Orientation, and the Counsel for Children Initiative. The funds are distributed among different organizations nationwide that provide the services. According to him, the sum is the same regardless of how many people the organizations are assisting, and they frequently raise extra money to pay for their expenses.

This time around, Trump is not targeting these programs like he did in his first administration.

When then-Attorney General Jeff Sessions declared in 2018 that the programs would no longer receive financing, the Justice Department changed its mind due to bipartisan backing from members of Congress and the threat of legal action from a group of groups that provide the services.

This time, the action was more sudden, with program workers being prohibited from detention facilities and the stop-work order being issued just hours before it went into force.

Due to the complexity of immigration law, many people wind up navigating the system without legal counsel because, unlike in criminal courts, they are not entitled to an attorney if they cannot afford one.

People may be in limbo for years due to the backlog of around 3.7 million cases in immigration courts across the nation. Advocates claim that hearings proceed more swiftly when people are prepared and have their affairs in order because judges are spared from having to go over the fundamentals with each person who comes before them. Additionally, because people are aware of the paperwork they must complete out and can receive assistance in accurately completing them, it helps shorten wait times at immigration court filing windows.

According to Edna Yang, co-executive director of American Gateways, which operates in three detention facilities and the immigration court in San Antonio, Texas, people can make educated decisions about whether to proceed with a case knowing their chances and the risks involved, or they can choose to just go home if they don’t want to go through a legal battle or don’t see any available relief that fits their situation.

According to Yang, the system won’t be fixed by discontinuing initiatives that genuinely assist individuals in obtaining the information they require. It will just exacerbate the situation.

According to activists, the groups also ensure that due process rights are upheld, notify individuals of impending filing deadlines, guarantee the availability of translators, and assist in preventing deportation orders that may forcibly remove asylum seekers to dangerous circumstances.

After four years in Mexico, Milagro, a 69-year-old Venezuelan woman, received an appointment through a U.S. government app and landed in the United States in May 2024. She is afraid that speaking up could impact her ongoing lawsuit, so the Associated Press agreed not to use her last name.

Citing fear for her life in Venezuela as a member of the political opposition, she submitted an asylum application. She applied for asylum in the immigration court in El Paso, Texas, using the aid desk run by Estrella del Paso because she was unemployed when she came. She learned that it was closed due to the stop-work order the previous time she visited.

She said in Spanish, “You feel a little frustrated because the window that you had open to ask, to get advice, is closed.” It is a sense of isolation and powerlessness.

She claimed that I would have been forced to pay money I don’t have if they hadn’t helped.

However, she worries that she may have to pay someone to assist her with a court appearance in February, which will require a large portion of her income as a caretaker for a 100-year-old woman.

____

Reporting was done by Associated Press writers Sophia Tareen in Chicago and Gisela Salomon in Miami.